– MEANING WHOM? AND DIFFERENT FROM WHOSE?

MM-N&Q-3

PURPOSE: To stimulate for response. To NOTE some interesting dots; and to QUERY–

1) Are there more related dots?;

2) Can these &/or other dots be connected meaningfully?

This report is not about comparative linguistics, but solely about WABANAKI ethnic-groups’ identities and their geographic boundaries in the early-17th-century, in the area now termed the Mid-Coast of Maine. French Jesuit Pierre Biard’s primary-source account being quoted and analyzed herein offers no word-list, and he makes only this single bald statement, seemingly about the particular group of Natives he was just discussing in some detail: ”The trouble was, that they have an altogether different language”– and thereby may hang a tale!

The group was chief Meteourmite’s people in the Kennebec-Sheepscot Rivers area, and the year was 1611. To my current knowledge, no modern scholar has been tempted to ponder (in print) Biard’s almost-400-year-old statement. I myself have wondered about it, yet avoided poking at it, for over thirty years. However, now I must take it on, because recently too many fellow researchers have asked me ”simple” questions that this odd tidbit just might help to answer.

Historical archaeology research now ongoing at the Popham Colony site in Phippsburg, the Colonial Pemaquid projects in Bristol, and even the Chouacoet site in Biddeford, all might be enhanced by someone’s figuring-out the Whom and the Whose of my sub-title above. Also, in the process, some balm might be found for helping to calm the pleas from the Davistown Museum website, for some scholarly recognition of the Wawenocks, ironically despite the DM’s dislike of French sources.

I’ll start by saying that, although it’s easy to ask: who were the WAWENOCKS?, and where? and when?, it’s hard to answer in an ethnohistorically relevant and meaningful way, because they just do not jump out of the early PRIMARY-SOURCES, even though they may abound in later secondary-sources & local-histories. So, the question should be: was or was not BIARD referring to an ethnic-entity (a distinct people or band) that, at that time (1611), could properly be termed as ”Wawenocks”, in his comment about ”an altogether different language” group? If he was, and if it could be, then this is the earliest specific primary-source about them. And, if not them, who were these people, there and then? We may never find out enough information, but we can start looking.

”What’s in a name?” — MUCH indeed, given the very fluid nature of Wabanaki societies! Biard’s 1611 comment came after a 1605 list & a 1607 raid, but before a 1615 killing & a 1616-19 pandemic & 1623-24 exploration’s account — any of which either gave us baseline data or caused changes in prior data. And the later publication-dates of older data should not confuse us. Flexibility & mobility of Wabanaki groups was their major adaptive trait for survival — changes of groupings & locations became a constant for them. Even voluntarily changing both leaders and followers became a regular means of coping. I call all this Dawnland Dynamics: the very essence of the Wabanaki Encounter.

CONTEXT & TIMING ARE KEY TO UNDERSTANDING

My accompanying CONTEXT-CALENDAR highlights major events in overall WABANAKI FRONTIER ENCOUNTERS, from the 1604 French settlement on St-Croix Island to the 1625 long-belated publication of “Description of the Countrey of MAWOOSHEN” by English travel-logger PURCHAS. By 1625, all three of the Encounter”s TRIPLE-WHAMMY factors had begun:

1st) Native Trade-Wars;

2nd) European-Disease Epidemics;

3rd) European Usurpation (English Push / French Pull)

Many of these major events became linked together over time, and each of them must be seen in the context & timing of the others to be best understood. The few primary-source Authors’ Names are underlined for easy identification.

Wherever logical to do so in my CON-CAL, I have clumped obviously-related events, using only minimal wording for general clarity. However, this has meant omitting some specific details which did bridge some herein-unclumped events: eg, WAYMOUTH’s Wabanaki captives were taken to England in 1605 not only to be debriefed of the MAWOOSHEN data to aid the English in choosing where to locate the POPHAM COLONY, but they also were supposed to be returned to Maine to act as future guides & go-betweens for the English. The surviving incomplete POPHAM COLONY account mentions that returned-1605-captives NAHANADA & SKIDWARRES went off on their own to participate in what I call the Micmac Sack of Saco in Summer 1607, [ for which the French at Port Royal loaned MEMBERTOU firearms and shallops (= boats); otherwise this was only a battle in a totally-Native trade-war, now called the TARRANTINE War ], but it does not say on whose behalf N & S participated. Was it just as part of BASHABA’s Alliance providing mutual aid to the Chouacoet band of ARMOUCHIQUOIS? Or was there a third side (a Mid-Coast faction possibly) involved in that event &/or its aftermath (as I suggested in my 1975 paper ”Membertou’s Raid”)? The ”correct” answer certainly would be helpful to this present case’s outcome.

All three early French writers (CHAMPLAIN, LESCARBOT, & BIARD), from their Bay of Fundy (aka ”French Bay”) base among the ”SOURIQUOIS” (=MICMAC) Native people, stated that the ET(E)CHEMIN were their next-westerly people [dwelling from the St-John River to the Kennebec River — ie, including the Penobscot River], and that to the west of the Kennebec River dwelt the AL(or AR)MOUCHIQUOIS people [a slur-name slung by the Micmac, not used again after Biard].

(Today, we can see that some easternmost Armouchiquois must have been Abenaki-Pennacook, in later terminology. A & P are hyphenated here because it is now impossible to know where & when the two separated if they did. Indeed, by the mid-17th century, Pennacook superchief Passaconaway had married-out his kinfolk eastward into his own personal alliance, as Bashaba had done westward.)

So, according to these three early French general statements, today’s Mid-Coast Maine must have been ET(E)CHEMIN country at that time (1604-1611). Yet BIARD, who was a French Jesuit missionary much in need of knowing who the Natives were and how to learn their languages so as to ”convert” them, seems to go against his own (and Champlain’s and Lescarbot’s) general statement(s) with his specific remark about sakamo METEOURMITE’s band of Natives whom he met in the Kennebec-Sheepscot Rivers area — the implication being both that they dwelt there and that they were those who had an ”altogether different language”, implying different than either Etechemin or Armouchiquois (or Souriquois), but conceivably only a different dialect of Abenaki, distinct from the Algonquian languages & dialects of other groups around them.

Unlike the French, the early English accounts did not use those three large-area group-names (S,E,A) for the peoples we now know collectively as Wabanakis. However, WAYMOUTH / ROSIER, POPHAM COLONY, & SMITH, (and belatedly PURCHAS), all told about superchief BASHABA &/or his MAWOOSHEN Alliance. This is a bit odd, because no English explorer apparently ever actually met Bashaba in person, while neither Champlain nor Biard (the two Frenchmen who did meet Bashaba in person) wrote him up as quite the superchief that the unmet Englishmen did. The major enemies of Bashaba, who invaded & killed him in 1615, were called TARRANTINES by the early English. [Because they invaded (ie, expanded for awhile) the T-Name wrongly got extended by later careless scholarship to the Penobscot River-&-Bay area Natives, alas.]

We now see those Tarrantines as a former alliance of Micmacs and Eastern Etchemins, who either traded or raided with other, more-westerly, Wabanaki peoples: exchanging surplus European goods they obtained directly in the Gulf of St-Lawrence for furs, in return getting maize (= corn) & more furs-to-trade from the westerly Gulf of Maine peoples. The latter had only belated direct-trade-contacts with Europeans; the former began them much earlier, in the 1500s. Native trade-wars were common throughout North America. Haughtiness in trading of European metal & cloth goods or violence in raiding maize & furs-to-trade made enemies of traditional Native exchange-system allies.

The 1625 PURCHAS belated account titled ”The Description of the Countrey of MAWOOSHEN” tells the probably-1605 data of eleven Maine rivers. It names their Native ”Townes” & leaders, and numbers their houses & warriors. From east to west, the rivers seem to be from today’s Union River to today’s Saco River. That entirety was called MAWOOSHEN and was BASHABA’s own personal Alliance formed by his own descent & prestige, and the carefully-married-out-web of his kinfolk.

MAWOOSHEN seems to translate as ”Walking-Together” — a fine analogy for a political alliance.

Except for naming Bashaba’s Alliance MAWOOSHEN and his enemies TARRANTINES, early English accounts tended to name Wabanaki groups after the rivers or villages on / in which they were encountered — eg: Sheepscot; Pemaquid. Wabanaki seasonal migrations and fluid societies frequently befuddled the rigidly land-tenure-oriented English Colonials and their nomenclature.

In summary, it seems that the English were too specific, and the French were too general, in their group-namings of Northeastern Algonquian peoples — especially so for Wabanaki subdivisions.

WAYMOUTH’s 1605 Five WABANAKI Captives have been group-named many different ways; herein I use the ”safest” name for them — the general / generic term WABANAKI (= Dawn-land-ers) — but even that may not apply to one of them, whom ROSIER listed last and noted as a ”Servant”, which could mean anything from a Mohawk war-captive (slave) to an elite suitor from another band (even from a non-Wabanaki people) doing ”bride-service” for his future inlaws. Rosier also noted the first-listed of The 5 as ”a Sagamo or Commander” and the next three as ”Gentlemen”.

PURCHAS, in another listing of The 5, also noted Rosier’s Sagamo as BASHABA’s ”Brother”, and the top-listed of Rosier’s three Gentlemen as ”his Brother”, implying that the former was perhaps both older and more prestigious. Indeed, in 1607, we learn that the Sagamo captive, who had been returned in 1606, was then head-sakamo of Pemaquid village band. This was NAHANADA (in very different spellings). The #2-man AMO(O)RET is lost to history, although he may have been returned with Nahanada and then gone elsewhere. [The mobility of Wabanaki sakamos, both to be leaders of other bands or villages and to make long-distance visits &/or trading expeditions, coupled with occasional name-changing, or having multiple names (beyond European tone-deaf hearing-spelling variations), complicates our understanding of who was who and where and why — eg, SAMOSET in the 1620s (see CON-CAL).]

The Five Captives apparently were taken by the English while fishing, in the George’s Islands area south of St-George River-mouth, at the southernmost end of the western shore of Penobscot Bay. In French terms, this was ET(E)CHEMIN territory. But the vocabulary that ROSIER learned from The 5 is not easily classified by modern linguistic scholars, because it seems to be a mixture of known Wabanaki languages-&-dialects and some unknowns. However, labeling of Rosier’s vocabulary with the catch-all term ”Eastern Abenaki” by some linguists is simply no longer satisfactory for that area at that time (1605) — as if it were then a today’s Penobscot Nation wordlist. The societal movements of the Wabanaki peoples over time requires fuller consideration here, to make labeling meaningful.

After Frenchmen CHAMPLAIN and BIARD met BASHABA in person, respectively in 1604 up Penobscot River near today’s Bangor, and in 1611 up Penobscot Bay near modern Castine, they both called him an ET(E)CHEMIN chief. (I would add Western Etchemin, because he had Eastern Etchemin enemies.) The Western Etchemin occupied the Penobscot drainage, and then moved eastward, before today’s Penobscot Nation (an Eastern Abenaki people) moved into it; both peoples were equally Wabanaki in the generic sense that term means today and implies for the historic past.

PURCHAS’s noting NAHANADA and AMO(O)RET as Bashaba’s ”Brothers”, and the POPHAM COLONY account’s noting that Nahanada was head sakamo at Pemaquid, together indicate the extent of Bashaba’s kinship influence in the Mid-Coast region. ”Brotherhood” could be by adoption, or by half-brotherhood through polygyny, if not meaning by full siblingship. MAWOOSHEN had to have been a polyglot & inter-ethnic-group alliance to extend as far as it did, whether in the French three general terms of ethnicity or in the English much-more-specific group-namings. Bashaba must have had to know neighboring dialects & languages, or at least have had an interpreter-corps at work (as today’s Wabanaki Confederacy needs: when not speaking English or French, it might hear any or all: Micmac, Maliseet-Passamaquoddy, Eastern Abenaki, Western Abenaki, or ”Central”Abenaki.).

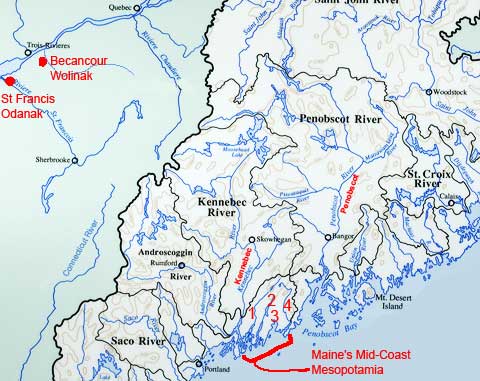

East of Kennebec River, West of Penobscot River with four rivers of its own:

1: Sheepscot River

2: Damariscotta River

3: Medomak River

4: St George River

Map adapted by PC**2 & Assc’s(TM) from part of the “Gulf of Maine Watershed” map by Richard D Kelly Jr, 1991, Maine State Planning Office, Augusta, Maine

MAINE’S MID-COAST MESOPOTAMIA

In calling the ”Land Between the Rivers” Kennebec and Penobscot Mesopotamia, I am not implying that a Cradle of Civilization occurred therein — although it was a cradle of European fisheries in the Gulf of Maine. I have in mind the disagreeable aspects of Civilization, terminologically. This Maine Mesopotamia is a real Tower of Babel, where one person’s Mede is another person’s Persian, and the French even misspelled their Acadia (let alone agreed upon its boundary with the English). There is so little to be agreeable about, that disagreement is inevitable in studying the area. Newly available books prove that beyond a doubt! One tells us Mawooshen means ”to eat noble meat”. This prompts me to ask: Is it possible both to walk-together [my choice] and to eat noble meat at the same time?

|

The early Primary Sources do little more than verify the mere existence of METEOURMITE, when we run him through those academic check-points, in the time-sequential-order of those early writers who either encountered him or reported about him, and those who did not do so. See below. |

|

|

1 CHAMPLAIN |

MANTHOUMERMER (a long-winded chief with many attendants)* |

| 2 LESCARBOT (HNF) |

O |

|

3 Waymouth-ROSIER |

O |

| 4 PURC Add to ROSI | MENTEOLMET Name #7 on a list of 12 Chiefs |

| 5 PURC Mawoo data | MENTAURMET Aponeg River, Nebamocago Town, 160 hh, 300 m |

| 6 LESCARBOT (Epic) | O? (or ”MNESINOU”? — or was SASINOU intended here? — or both?) |

| 7 POPHAM COLONY | O |

| 8 BIARD | METEOURMITE ”an altogether different language” (+ * above) |

| 9 HARLOW-Hobson | MENT(ER)OERMIT(T) (Harlow suggests Hobson use M as a guide) |

| 10 SMITH | O |

| 11 LEVETT | Me/aNAWORMET (L met M at Southport I, with SAMOSET et al) |

| 12 PURC Mawoo publ | See 5 above |

“PEOPLE OF THE BAYS”

Fannie Hardy Eckstorm (1865-1946), Maine’s first ethnohistorian of the Wabanaki peoples, has left us only a few tidbits about the WAWENOCKS, mostly without dated historical contexts, alas: ”According to Dr.[Frank] Speck, the name … comes from Walinakiak, the ‘People of the Bays’, their old homes having been along the deeply indented coast between the Kennebec and St.George’s Rivers, whence their other name of ‘Sheepscot Indians’. ” (Old John Neptune…1945:74) ”The coastwise Wawenocks … had to retire to Canada … or mingle with the eastern tribes.” (p 79) [ — retire or mingle meaning move out, because of English push.]

However, Eckstorm drops a hint of some importance for us to consider, in an isolated remark whose full meaning is left undeveloped by her, but on which I think one of our issues herein depends. It might also help to explain why Eckstorm had so very little to say about the Wawenocks per se: ”Other tribes would call them Walinakiak ‘Bay Folk,’ but not they themselves.” (OJN p 75) This well could mean that the name Wawenock would not appear at all in early primary sources, and would start into usage only after the people it was applied to had moved in sufficient numbers into an area where they were newcomers and would need a new name telling where they were from — eg, when they moved to a French missionary-village in southern Quebec, because of French pull.

The earliest primary source about the Wawenocks that I now know of is the simple reference to their group-existence, in the 1721 letter written by French Jesuit Sebastien Rale at Norridgewock mission-village on the upper Kennebec River, for ”the Eastern Indians”, to Massachusetts Colonial Governor Samuel Shute. Therein, the name ”8AN8INAK” [”8” = the sound ”wuh”] is listed last among eleven total groups of ”the Abanaquis nation” who were signing the letter.

The placement of the Wawenock name at the end of that 1721 list, and just after the name of their current Quebec neighbors the ”ARSIKANTE8” ( = St-Francis / ODANAK), implies to me that, at that time (1721), most of the Wawenocks already had moved to southern Quebec Province. Today, the WOLINAK Band of Abenaquis still lives at Becancour / WOLINAK, on the Becancour River, near the south shore of the St-Lawrence River — just east across it from the city of Trois-Rivieres QC. The ODANAK Band of Abenaquis is not far away, to the southwest, on the St-Francois River.

THE PRINCIPLE OF PARSIMONY, aka OCCAM’S RAZOR

Without another separate ethnic-name-group (Wawenock) in Maine’s Mid-Coast Mesopotamia in the early 1600s, the early French general description of that area as Et(e)chemin territory can stand firm. And, finally and most importantly, when Biard wrote that ”they have an altogether different language”, he well may not have been singling-out just Meteourmite’s people from, but combining them with, all the Wabanaki peoples together, and comparing all of their languages collectively to the French language! So, without another separate language for them, then Meteourmite’s people can be seen simply as a specific Et(e)chemin band, within general Et(e)chemin territory. This collective interpretation of Biard’s statement could simplify our issue by removing it entirely.

The Principle of Parsimony (ie, getting the most for the least given) states that the most-likely explanation is the best explanation, at least until further evidence can rule it out. Using Eckstorm’s ”not they themselves” stimulus, I believe that my responses as just stated are both parsimonious and a good opportunity to rest the case, for the moment at least — but I’m still open for other opinions.

|

CONTEXT-CALENDAR for PRIMARY-SOURCES

on WABANAKI Peoples,

1604 — 1625, by Frenchmen CHAMPLAIN, LESCARBOT, & BIARD; and for Englishmen WAYMOUTH (by ROSIER), & POPHAM (by others), by HARLOW, SMITH, & LEVETT, and about BASHABA’s MAWOOSHEN ALLIANCE (by PURCHAS, from HAKLUYT, but probably largely through ROSIER & GORGES, from 5 Male WABANAKI Captives of 1605). |

|

|

1604

|

St-Croix Island First French Settlement Attempt (se of Calais ME on NB Border) |

|

1604-07

|

CHAMPLAIN‘s Gulf of Maine Coastal Explorations — (He Met BASHABA 16 Sep 1604 near today’s Bangor ME on Penobscot River); (He Met MANTHOUMERMER July 1605 in Kennebec-Sheepscot Rivers area). |

|

1605

|

Port Royal French (Re-)Settlement Began (e of Digby NS). |

|

1605

|

WAYMOUTH‘s Maine Coastal Explorations –(He Did Not Meet BASHABA, but is Said to have Kidnapped 2 of B‘s ”Brothers”);(He Kidnapped 5 WABANAKI Men whose Debriefing led to the ”Description of the Countrey of MAWOOSHEN” [BASHABA‘s] which was Not Published Until 1625). |

|

1606

|

NAHANADA Returned to Pemaquid ME Area with HANNAM-&-PRING‘s Voyage, which may also have Returned? AMORET. |

|

1607

|

MEMBERTOU’s Raid on Chouacoet ALMOUCHIQUOIS — (the MICMAC Sack of Saco ME), an Early Battle in TARRANTINE WAR (See EpicPoem by LESCARBOT). |

|

1607

|

SKIDWARRES Returned to Sagadahoc ME Area with POPHAM COLONY Voyage. |

|

1607-08

|

POPHAM COLONY First English Settlement Attempt, but Quit (s of Bath ME) –(Full-Term Accounts Lost; Apparently Wanted to Meet BASHABA but Did Not do so). |

|

1610

|

MEMBERTOU Became First Baptised-Christian Chief in Northeast (at Port Royal). |

|

1611

|

BIARD Arrived at Port Royal, and Explored Coast from St-John to Kennebec Rivers — (He Met METEOURMITE in late-Oct / early-Nov 1611 in Kenne-Sheep Rivers area); (He Met BASHABA on or about 7 Nov 1611 near the Mouth / Bay of Penobscot River). |

|

1613

|

St-Sauveur Mission Started at Somes Sound on Mt-Desert Island by French (BIARD). |

|

1613

|

ARGALL’s Raid Destroyed All 3 French Settlements in Acadia (SSM, SCI, & PR) — (BIARD was Captured at SSM and Taken Back to Europe). |

|

1614

|

HARLOW‘s Variation

of [MAWOOSHEN] Info, Extended sw for HOBSON Voyage,which

Returned SASSACOMOIT. / |

|

1614

|

SMITH‘s Exploration of ”New England” Coast — (He Claimed Aid of NAHANADA); (He Did Not Meet BASHABA, but Wrote About B‘s Far-Flung Influence). |

|

1615

|

BASHABA was Killed by a TARRANTINE Raid, Many of His Allies Were Dispersed &/or Fought Among Themselves, and Thus His MAWOOSHEN Alliance Crumbled. |

|

1616-19

|

”GREAT PLAGUE” Pandemic Decimated Natives from Cape Cod to Penobscot Bay. |

|

1620

|

PLYMOUTH COLONY English Settlement Began (”PILGRIMS” at Plymouth MA). |

|

1621

|

SAMOSET Visited Plymouth Colony, Introduced Patuxet Wampanoag SQUANTO to the Pilgrims, & Then Returned Home to the Pemaquid ME Area. |

|

1623-24

|

LEVETT Explored n&s of Casco Bay & was Adopted as SAMOSET-et-al’s ”Cousin”. |

|

1625

|

”SAMOSET’s Deed” to John Brown: It is Now Considered a Century-Later Forgery. |

|

1625

|

”DESCRIPTION of the Countrey of MAWOOSHEN” Published by PURCHAS — 2 Full Decades After Many on its Lists of Places, Peoples, & Persons were Long-Gone Via Warfare, Pandemic, Community-Regroupings, Political-Eclipses, & Plain-Old-Age. |